Middle Assyrian Empire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Middle Assyrian Empire was the third stage of

Ashur-uballit, doubtlessly watching the conflict between Mitanni and the Hittites closely out of interest in expanding Assyria, directed much of his attention to the lands south of his realm. Successful campaigns were directed against both

Ashur-uballit, doubtlessly watching the conflict between Mitanni and the Hittites closely out of interest in expanding Assyria, directed much of his attention to the lands south of his realm. Successful campaigns were directed against both

Under the warrior-kings Adad-nirari I ( 1305–1274 BC),

Under the warrior-kings Adad-nirari I ( 1305–1274 BC),

Shalmaneser I's son Tukulti-Ninurta I became king 1243 BC. He had, according to historian Stefan Jakob, "an unconditional will to create something that would last forever" and his wide-ranging conquests brought the Middle Assyrian Empire to its greatest extent. Even before he became king, neighboring kingdoms had been wary of his accession; when he assumed the throne, the Hittite king

Shalmaneser I's son Tukulti-Ninurta I became king 1243 BC. He had, according to historian Stefan Jakob, "an unconditional will to create something that would last forever" and his wide-ranging conquests brought the Middle Assyrian Empire to its greatest extent. Even before he became king, neighboring kingdoms had been wary of his accession; when he assumed the throne, the Hittite king

Inscriptions from the late reign of Tukulti-Ninurta showcase increasing internal isolation, as many among the powerful nobility of Assyria grew dissatisfied with his rule, especially after the loss of Babylonia. In some of his own inscriptions, Tukulti-Ninurta appears to lament the losses since his glory days. His long and prosperous reign ended with his assassination, which was followed by inter-dynastic conflict and a significant drop in Assyrian power. Though some historians have attributed the assassination to Tukulti-Ninurta's moving the capital away from Assur, a possibly sacrilegious act, it is more probable that it was the result of the growing dissatisfaction during his late reign. Later chroniclers blame the assassination on his son Ashur-nasir-apli, perhaps a misspelled version of the name of his successor

Inscriptions from the late reign of Tukulti-Ninurta showcase increasing internal isolation, as many among the powerful nobility of Assyria grew dissatisfied with his rule, especially after the loss of Babylonia. In some of his own inscriptions, Tukulti-Ninurta appears to lament the losses since his glory days. His long and prosperous reign ended with his assassination, which was followed by inter-dynastic conflict and a significant drop in Assyrian power. Though some historians have attributed the assassination to Tukulti-Ninurta's moving the capital away from Assur, a possibly sacrilegious act, it is more probable that it was the result of the growing dissatisfaction during his late reign. Later chroniclers blame the assassination on his son Ashur-nasir-apli, perhaps a misspelled version of the name of his successor

Ashur-resh-ishi's son and successor

Ashur-resh-ishi's son and successor

The Assyrian kings never ceased to believe that the lost lands would eventually be retaken. In the end, the collapse of the Hittites and the Egyptian lands in the Levant benefitted Assyria; with the old empires shattered, the fragmented territories surrounding the Assyrian heartland would eventually prove to be easy conquests for the Assyrian army. The reign of

The Assyrian kings never ceased to believe that the lost lands would eventually be retaken. In the end, the collapse of the Hittites and the Egyptian lands in the Levant benefitted Assyria; with the old empires shattered, the fragmented territories surrounding the Assyrian heartland would eventually prove to be easy conquests for the Assyrian army. The reign of

Middle Assyrian royal palaces were prominent symbols of royal power, and the centers and main institutions of the Assyrian government. Though the main palace was located in Assur, kings had palaces at several different sites which they often traveled between. The most important surviving source concerning Middle Assyrian royal palaces are the Middle Assyrian palace decrees, a set of documents composed either late in the reign of Tiglath-Pileser I or in the reigns of his immediate successors. These documents contain a large number of regulations on the personnel of the palaces and their roles and duties, in particular the women. These regulations differentiate between the "wife of the king" (''aššat šarre''), what modern historians would term the "queen", and a group of "palace women" (''sinniltu ša ekalle''), i.e. a royal

Middle Assyrian royal palaces were prominent symbols of royal power, and the centers and main institutions of the Assyrian government. Though the main palace was located in Assur, kings had palaces at several different sites which they often traveled between. The most important surviving source concerning Middle Assyrian royal palaces are the Middle Assyrian palace decrees, a set of documents composed either late in the reign of Tiglath-Pileser I or in the reigns of his immediate successors. These documents contain a large number of regulations on the personnel of the palaces and their roles and duties, in particular the women. These regulations differentiate between the "wife of the king" (''aššat šarre''), what modern historians would term the "queen", and a group of "palace women" (''sinniltu ša ekalle''), i.e. a royal

Some regions of the Assyrian realm were outside of the provincial framework but still subject to the Assyrian kings, these included vassal states ruled by lesser kings, such as the Mitanni lands governed by the grand viziers. Under the provincial governors, cities also had their own administrations, headed by mayors (''ḫazi’ānu''), appointed by the kings but representing the local city elite. Similar to the governors, though less important, the mayors were mostly responsible for local economy, including overseeing rations, agriculture and organization of labor.

The Assyrians also employed what they referred to as the ''ilku'' system, not entirely unlike the

Some regions of the Assyrian realm were outside of the provincial framework but still subject to the Assyrian kings, these included vassal states ruled by lesser kings, such as the Mitanni lands governed by the grand viziers. Under the provincial governors, cities also had their own administrations, headed by mayors (''ḫazi’ānu''), appointed by the kings but representing the local city elite. Similar to the governors, though less important, the mayors were mostly responsible for local economy, including overseeing rations, agriculture and organization of labor.

The Assyrians also employed what they referred to as the ''ilku'' system, not entirely unlike the

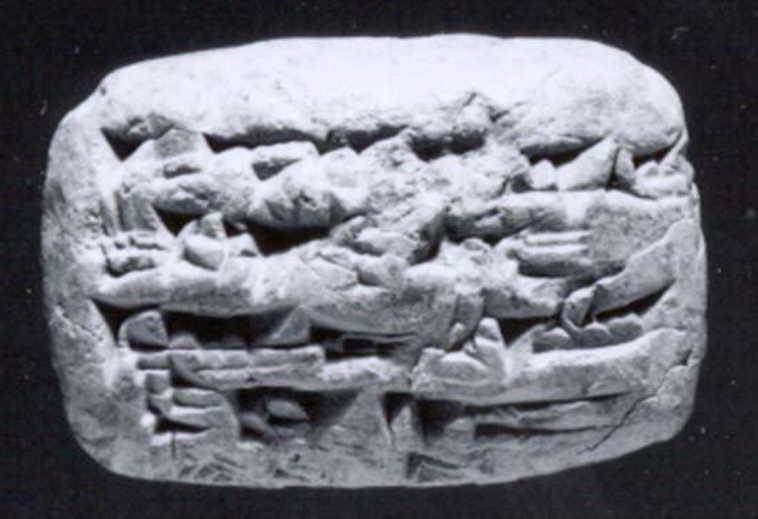

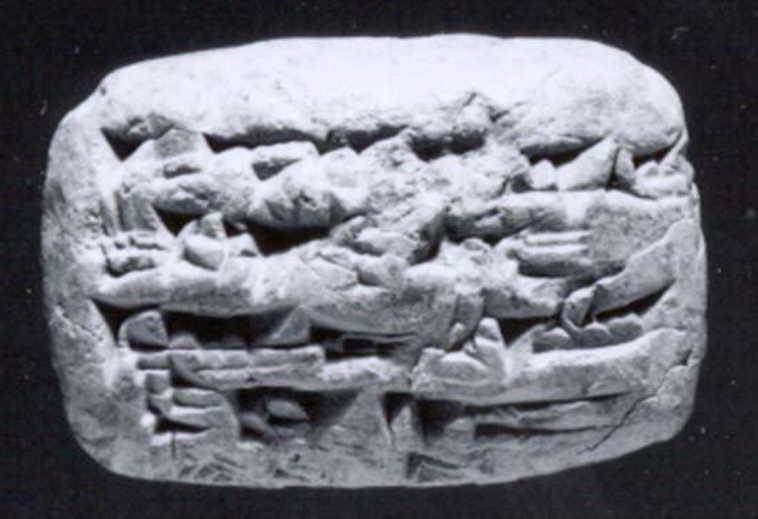

In order for the large construction projects and military activities of the Middle Assyrian kings to have been possible, the Middle Assyrian Empire employed a sophisticated system of recruiting and administrating personnel. To keep track of and administrate the diverse people under imperial control, a specific type of waxed tablets, dubbed ''le’ānū'' (''le’ū'' in singular form), were employed. These tablets, attested from the time of Adad-nirari I onwards, summarized data on the available manpower, calculated required rations and provisions and documented responsibilities and tasks. According to administrative records on construction work at the royal palaces of Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta and Assur, these projects were completed with workforces of about 2,000 men, divided into recruits from various cities (''ḫurādu''), mostly gathered through the ''ilku'' system, engineers or architects (''šalimpāju''), carpenters and religious functionaries.

The taxation system of the Middle Assyrian Empire is not yet fully understood. Though tax collectors are known to have existed, records of taxes being collected and what these were are lacking; the only currently confidently attested direct tax paid by individuals was an import tax, levied on imports of goods from foreign states. In at least one case, this tax amounted to about 25 percent of the purchase price. Some documents also mention the ''ginā’u'' tax, which had some connection to the provincial governments. Other economically important sources of money for the empire included plundering conquered territories, which reduced the cost of the campaign that had conquered them, continuous tribute (''madattu'') from vassal states, as well as "audience gifts" (''nāmurtu'') from foreign rulers and powerful individuals. These gifts could sometimes be carry large value for the empire itself; one documents attests that a gift given to Ninurta-tukulti-Ashur while he was still a prince in the reign of his father Ashur-dan I included 914 sheep.

In order for the large construction projects and military activities of the Middle Assyrian kings to have been possible, the Middle Assyrian Empire employed a sophisticated system of recruiting and administrating personnel. To keep track of and administrate the diverse people under imperial control, a specific type of waxed tablets, dubbed ''le’ānū'' (''le’ū'' in singular form), were employed. These tablets, attested from the time of Adad-nirari I onwards, summarized data on the available manpower, calculated required rations and provisions and documented responsibilities and tasks. According to administrative records on construction work at the royal palaces of Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta and Assur, these projects were completed with workforces of about 2,000 men, divided into recruits from various cities (''ḫurādu''), mostly gathered through the ''ilku'' system, engineers or architects (''šalimpāju''), carpenters and religious functionaries.

The taxation system of the Middle Assyrian Empire is not yet fully understood. Though tax collectors are known to have existed, records of taxes being collected and what these were are lacking; the only currently confidently attested direct tax paid by individuals was an import tax, levied on imports of goods from foreign states. In at least one case, this tax amounted to about 25 percent of the purchase price. Some documents also mention the ''ginā’u'' tax, which had some connection to the provincial governments. Other economically important sources of money for the empire included plundering conquered territories, which reduced the cost of the campaign that had conquered them, continuous tribute (''madattu'') from vassal states, as well as "audience gifts" (''nāmurtu'') from foreign rulers and powerful individuals. These gifts could sometimes be carry large value for the empire itself; one documents attests that a gift given to Ninurta-tukulti-Ashur while he was still a prince in the reign of his father Ashur-dan I included 914 sheep.

There was no standing army in the Middle Assyrian period. Instead, the majority of soldiers used for military engagements were mobilized only when they were needed, such as for civil projects or in the time of campaigns. Large amounts of soldiers could be recruited and mobilized relative quickly on the basis of legal obligations and regulations. It is impossible to ascertain from the surviving inscriptions the extent to which Middle Assyrian levies were trained for their tasks, but it is unlikely that the Assyrian army would be able to be as successful as it was in the reigns of figures like Tukulti-Ninurta I and Tiglath-Pileser I without trained soldiers. In addition to the levies, who are called ''ḫurādu'' or ''ṣābū ḫurādātu'' in the inscriptions, there was also a more experienced class of "professional" soldiers, called the ''ṣābū kaṣrūtu''. It is not clear what exactly separated the ''ṣābū kaṣrūtu'' from the other soldiers; perhaps the term included some certain branches of the army, such as archers and charioteers, who required more extensive training than normal

There was no standing army in the Middle Assyrian period. Instead, the majority of soldiers used for military engagements were mobilized only when they were needed, such as for civil projects or in the time of campaigns. Large amounts of soldiers could be recruited and mobilized relative quickly on the basis of legal obligations and regulations. It is impossible to ascertain from the surviving inscriptions the extent to which Middle Assyrian levies were trained for their tasks, but it is unlikely that the Assyrian army would be able to be as successful as it was in the reigns of figures like Tukulti-Ninurta I and Tiglath-Pileser I without trained soldiers. In addition to the levies, who are called ''ḫurādu'' or ''ṣābū ḫurādātu'' in the inscriptions, there was also a more experienced class of "professional" soldiers, called the ''ṣābū kaṣrūtu''. It is not clear what exactly separated the ''ṣābū kaṣrūtu'' from the other soldiers; perhaps the term included some certain branches of the army, such as archers and charioteers, who required more extensive training than normal  The foot soldiers appear to have been divided into the ''sạ bū ša kakkē'' ("weapon troops") and the ''sạ bū ša arâtē'' ("shield-bearing troops"). Surviving inscriptions do not specify what kind of weaponry these soldiers carried. In lists of the troops in armies, the ''sạ bū ša kakkē'' appear opposite the chariots, whereas the ''sạ bū ša arâtē'' appear opposite to the archers. It is possible that the ''sạ bū ša kakkē'' included ranged troops, such as slingers (''ṣābū ša ušpe'') and archers (''ṣābū ša qalte''). The chariots were a separate component of the army. Based on surviving depictions, chariots were crewed by two soldiers: an archer who commanded the chariot (''māru damqu'') and a driver (''ša mugerre''). Chariots were not used extensively before the time of Tiglath-Pileser I, who put particular emphasis on the chariots not just as a combat unit but also as the vehicle to be used by the king. Clear evidence of the special strategic importance of chariots comes from chariots forming their own branch of the army whereas cavalry (''ša petḫalle'') did not. When used, cavalry was often simply employed for escorting or message deliveries. Further specialized combat roles existed, including the

The foot soldiers appear to have been divided into the ''sạ bū ša kakkē'' ("weapon troops") and the ''sạ bū ša arâtē'' ("shield-bearing troops"). Surviving inscriptions do not specify what kind of weaponry these soldiers carried. In lists of the troops in armies, the ''sạ bū ša kakkē'' appear opposite the chariots, whereas the ''sạ bū ša arâtē'' appear opposite to the archers. It is possible that the ''sạ bū ša kakkē'' included ranged troops, such as slingers (''ṣābū ša ušpe'') and archers (''ṣābū ša qalte''). The chariots were a separate component of the army. Based on surviving depictions, chariots were crewed by two soldiers: an archer who commanded the chariot (''māru damqu'') and a driver (''ša mugerre''). Chariots were not used extensively before the time of Tiglath-Pileser I, who put particular emphasis on the chariots not just as a combat unit but also as the vehicle to be used by the king. Clear evidence of the special strategic importance of chariots comes from chariots forming their own branch of the army whereas cavalry (''ša petḫalle'') did not. When used, cavalry was often simply employed for escorting or message deliveries. Further specialized combat roles existed, including the

Because of the limited surviving material, information regarding social life and living conditions of the Middle Assyrian period is generally available in detail only for the socio-economic elite and upper classes of society. At the top of Middle Assyrian society were members of long-established and large families, called "houses", who tended to occupy the most important offices within the government. These houses were in many cases the descendants of the most prominent merchant families of the Old Assyrian period. It is clear from surviving documents that

Because of the limited surviving material, information regarding social life and living conditions of the Middle Assyrian period is generally available in detail only for the socio-economic elite and upper classes of society. At the top of Middle Assyrian society were members of long-established and large families, called "houses", who tended to occupy the most important offices within the government. These houses were in many cases the descendants of the most prominent merchant families of the Old Assyrian period. It is clear from surviving documents that

A sophisticated Assyrian imperial road system was created in the Middle Assyrian period. Though extensive road systems must have been employed in older civilizations as well, such as by the Hittites and Egyptians, the Middle Assyrian road system is the as of yet the earliest known such road system in the Ancient Near East, its creation perhaps stemming from the trading expertise of the Assyrians in the preceding Old Assyrian period. The road system of the Middle Assyrian Empire was the direct precursor of the sophisticated road systems of the succeeding Neo-Assyrian,

A sophisticated Assyrian imperial road system was created in the Middle Assyrian period. Though extensive road systems must have been employed in older civilizations as well, such as by the Hittites and Egyptians, the Middle Assyrian road system is the as of yet the earliest known such road system in the Ancient Near East, its creation perhaps stemming from the trading expertise of the Assyrians in the preceding Old Assyrian period. The road system of the Middle Assyrian Empire was the direct precursor of the sophisticated road systems of the succeeding Neo-Assyrian,

It is possible that the dominant military role of Ashur in the Middle Assyrian period was the result of the theology promulgated by the Amorite conqueror Shamshi-Adad I, who conquered Assur in the 19th century BC. Shamshi-Adad replaced the decaying original temple of Ashur in Assur with a new temple dedicated to the chief god of the Mesopotamian pantheon,

It is possible that the dominant military role of Ashur in the Middle Assyrian period was the result of the theology promulgated by the Amorite conqueror Shamshi-Adad I, who conquered Assur in the 19th century BC. Shamshi-Adad replaced the decaying original temple of Ashur in Assur with a new temple dedicated to the chief god of the Mesopotamian pantheon,

Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

n history, covering the history of Assyria from the accession of Ashur-uballit I

Ashur-uballit I ''(Aššur-uballiṭ I)'', who reigned between 1363 and 1328 BC, was the first king of the Middle Assyrian Empire. After his father Eriba-Adad I had broken Mitanni influence over Assyria, Ashur-uballit I's defeat of the Mitanni ...

1363 BC and the rise of Assyria as a territorial kingdom to the death of Ashur-dan II

Ashur-Dan II (Aššur-dān) (934–912 BC), son of Tiglath Pileser II, was the earliest king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. He was best known for recapturing previously held Assyrian territory and restoring Assyria to its natural borders, from Tur ...

in 912 BC. The Middle Assyrian Empire was Assyria's first period of ascendancy as an empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

. Though the empire experienced successive periods of expansion and decline, it remained the dominant power of northern Mesopotamia throughout the period. In terms of Assyrian history, the Middle Assyrian period was marked by important social, political and religious developments, including the rising prominence of both the Assyrian king

The king of Assyria (Akkadian: ''Išši'ak Aššur'', later ''šar māt Aššur'') was the ruler of the ancient Mesopotamian kingdom of Assyria, which was founded in the late 21st century BC and fell in the late 7th century BC. For much of its ear ...

and the Assyrian national deity Ashur.

The Middle Assyrian Empire was founded through Assur

Aššur (; Sumerian: AN.ŠAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: ''Aš-šurKI'', "City of God Aššur"; syr, ܐܫܘܪ ''Āšūr''; Old Persian ''Aθur'', fa, آشور: ''Āšūr''; he, אַשּׁוּר, ', ar, اشور), also known as Ashur and Qal'a ...

, a city-state through most of the preceding Old Assyrian period

The Old Assyrian period was the second stage of Assyrian history, covering the history of the city of Assur from its rise as an independent city-state under Puzur-Ashur I 2025 BC to the foundation of a larger Assyrian territorial state after the ...

, and the surrounding territories achieving independence from the Mitanni

Mitanni (; Hittite cuneiform ; ''Mittani'' '), c. 1550–1260 BC, earlier called Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian texts, c. 1600 BC; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat (''Hanikalbat'', ''Khanigalbat'', cuneiform ') in Assyrian records, or ''Naharin'' in ...

kingdom. Under Ashur-uballit, Assyria began to expand and assert its place as one of the great powers of the Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

. This aspiration chiefly came into fruition through the efforts of the kings Adad-nirari I ( 1305–1274 BC), Shalmaneser I

Shalmaneser I (𒁹𒀭𒁲𒈠𒉡𒊕 md''sál-ma-nu-SAG'' ''Salmanu-ašared''; 1273–1244 BC or 1265–1235 BC) was a king of Assyria during the Middle Assyrian Empire. Son of Adad-nirari I, he succeeded his father as king in 1265 BC.

Accord ...

( 1273–1244 BC) and Tukulti-Ninurta I

Tukulti-Ninurta I (meaning: "my trust is in he warrior godNinurta"; reigned 1243–1207 BC) was a king of Assyria during the Middle Assyrian Empire. He is known as the first king to use the title "King of Kings".

Biography

Tukulti-Ninurta I su ...

( 1243–1207 BC), under whom Assyria expanded to for a time become the dominant power in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

. The reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I marked the height of the Middle Assyrian Empire and included the subjugation of Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

and the foundation of a new capital city, Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, though it was abandoned after his death. Though Assyria was left largely unscathed by the direct effects of the Late Bronze Age collapse of the 12th century BC, the Middle Assyrian Empire began to experience a significant period of decline roughly at the same time. The assassination of Tukulti-Ninurta I 1207 BC led to inter-dynastic conflict and a significant drop in Assyrian power.

Even during its period of decline, Middle Assyrian kings continued to be assertive geopolitically; both Ashur-dan I

Aššur-dān I, m''Aš-šur-dān''(kal)an, was the 83rd king of Assyria, reigning for 46Khorsabad King List and the SDAS King List both read, iii 19, 46 MU.MEŠ KI.MIN. (variant: 36Nassouhi King List reads, 26+x MU. EŠ LUGAL-ta DU.uš.) years, c. ...

( 1178–1133 BC) and Ashur-resh-ishi I ( 1132–1115 BC) campaigned against Babylonia. Under Ashur-resh-ishi I's son and successor Tiglath-Pileser I

Tiglath-Pileser I (; from the Hebraic form of akk, , Tukultī-apil-Ešarra, "my trust is in the son of Ešarra") was a king of Assyria during the Middle Assyrian period (1114–1076 BC). According to Georges Roux, Tiglath-Pileser was "one of ...

(1114–1076 BC), the Middle Assyrian Empire experienced a period of resurgence, owing to wide-ranging campaigns and conquests. Tiglath-Pileser's armies marched as far from the Assyrian heartland as the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

. Though the reconquered and newly conquered lands were held on to for some time, the empire experienced a second and more catastrophic period of decline after the death of Tiglath-Pileser's son Ashur-bel-kala

Aššūr-bēl-kala, inscribed m''aš-šur-''EN''-ka-la'' and meaning “ Aššur is lord of all,” was the king of Assyria 1074/3–1056 BC, the 89th to appear on the ''Assyrian Kinglist''. He was the son of Tukultī-apil-Ešarra I, succeeded his ...

(1073–1056 BC), which saw the loss of most of the empire's territories outside of its heartlands, partly due to invasions by Aramean

The Arameans ( oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; syc, ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ, Ārāmāyē) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East, first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. The Aramean ...

tribes. Assyrian decline began to be reversed again under Ashur-dan II ( 934–912 BC), who campaigned extensively in the peripheral regions of the Assyrian heartland. The successes of Ashur-dan II and his immediate successors in restoring Assyrian rule over the empire's former lands, and in time going far beyond them, is used by modern historians to mark the transition from the Middle Assyrian Empire to the succeeding Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

.

Theologically, the Middle Assyrian period saw important transformations of the role of Ashur. Having originated as a deified personification of the city of Assur itself sometime centuries earlier in the Early Assyrian period

The Early Assyrian period was the earliest stage of Assyrian history, preceding the Old Assyrian period and covering the history of the city of Assur, and its people and culture, prior to the foundation of Assyria as an independent city-state unde ...

, Ashur in the Middle Assyrian period became equated with the old Sumerian head of the pantheon, Enlil

Enlil, , "Lord f theWind" later known as Elil, is an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with wind, air, earth, and storms. He is first attested as the chief deity of the Sumerian pantheon, but he was later worshipped by the Akkadians, Bab ...

, and was as a result of Assyrian expansionism and warfare transformed from a primarily agricultural god into a military one. The transition of Assyria from a city-state into an empire also had important administrative and political consequences. While the Assyrian rulers of the Old Assyrian period had governed with the title ''iššiak'' ("governor") jointly with a city assembly made up of influential figures from Assur, the Middle Assyrian kings were autocratic rulers who used the title ''šar'' ("king") and sought equal status to the monarchs of other empires. The transition into an empire also led to the development of various necessary systems, such as a sophisticated road system, various administrative divisions of territory and a complex web of royal administrators and officials.

History

Formation and rise

Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

became an independent territorial state under Ashur-uballit I

Ashur-uballit I ''(Aššur-uballiṭ I)'', who reigned between 1363 and 1328 BC, was the first king of the Middle Assyrian Empire. After his father Eriba-Adad I had broken Mitanni influence over Assyria, Ashur-uballit I's defeat of the Mitanni ...

1363 BC, having previously been under the suzerainty of the Mitanni

Mitanni (; Hittite cuneiform ; ''Mittani'' '), c. 1550–1260 BC, earlier called Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian texts, c. 1600 BC; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat (''Hanikalbat'', ''Khanigalbat'', cuneiform ') in Assyrian records, or ''Naharin'' in ...

kingdom. Though the transition of Assyria from being merely a city-state around Assur

Aššur (; Sumerian: AN.ŠAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: ''Aš-šurKI'', "City of God Aššur"; syr, ܐܫܘܪ ''Āšūr''; Old Persian ''Aθur'', fa, آشور: ''Āšūr''; he, אַשּׁוּר, ', ar, اشور), also known as Ashur and Qal'a ...

(as it was throughout most of the preceding Old Assyrian period

The Old Assyrian period was the second stage of Assyrian history, covering the history of the city of Assur from its rise as an independent city-state under Puzur-Ashur I 2025 BC to the foundation of a larger Assyrian territorial state after the ...

) had begun already in the last few decades under Mittani suzerainty, it is the independence achieved under Ashur-uballit, as well as Ashur-uballit's conquests of nearby territories, such as the fertile region between the Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

, the foothills of the Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains ( Turkish: ''Toros Dağları'' or ''Toroslar'') are a mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolian Plateau. The system extends along a curve from Lake Eğird ...

and the Upper Zab, which modern historians use to mark the beginning of the Middle Assyrian period.

Ashur-uballit was the first native Assyrian ruler to claim the royal title ''šar'' ("king"), and the first ruler of Assur to do so since the time of the Amorite

The Amorites (; sux, 𒈥𒌅, MAR.TU; Akkadian: 𒀀𒈬𒊒𒌝 or 𒋾𒀉𒉡𒌝/𒊎 ; he, אֱמוֹרִי, 'Ĕmōrī; grc, Ἀμορραῖοι) were an ancient Northwest Semitic-speaking people from the Levant who also occupied lar ...

conqueror Shamshi-Adad I

Shamshi-Adad ( akk, Šamši-Adad; Amorite: ''Shamshi-Addu''), ruled 1808–1776 BC, was an Amorite warlord and conqueror who had conquered lands across much of Syria, Anatolia, and Upper Mesopotamia.Some of the Mari letters addressed to Shamsi-Ad ...

in the 18th century BC. Shortly after achieving independence, he further claimed the dignity of a great king on the level of the pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: ''pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the an ...

s and the Hittite kings The dating and sequence of the Hittite kings is compiled from fragmentary records, supplemented by the recent find in Hattusa of a cache of more than 3500 seal impressions giving names and titles and genealogy of Hittite kings. All dates given here ...

. Ashur-uballit's claim to be a great king meant that he also embedded himself in the ideological implications of that role; a great king was expected to expand the borders of his realm to incorporate "uncivilized" territories, ideally eventually ruling the entire world. On account of political realism however, the true situation was most often diplomacy with adversaries of equal rank, such as Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

, and conquest only of smaller and military inferior states in the near vicinity. Ashur-uballit's reign was often regarded by later generations of Assyrians as the true birth of Assyria. The term "land of Ashur" (''māt Aššur''), i.e. designating Assyria as comprising a larger kingdom, is first attested as being used in his time.

The rise of Assyria was intertwined with the decline and collapse of its former suzerain, Mitanni. Assyria was subjugated by Mittani 1430 BC, and as such spent about 70 years under Mitanni rule. Chiefly responsible for bringing an end to Mitanni dominance in northern Mesopotamia was the Hittite king Šuppiluliuma I

Suppiluliuma I () or Suppiluliumas I () was king of the Hittites (r. c. 1344–1322 BC ( short chronology)). He achieved fame as a great warrior and statesman, successfully challenging the then-dominant Egyptian Empire for control of the lands bet ...

, whose 14th century BC war with Mitanni over control of Syria effectively led to the beginning of the end of the Mitanni kingdom. It was in this struggle for supremacy and hegemony that Ashur-uballit secured independence. The Mittani-Hittite conflict was preceded by a period of weakness in the Mitanni kingdom; the heir to the Mitanni throne, Artashumara

Artashumara Akkadian: ), brother of Tushratta and son of Shuttarna II, briefly held the throne of Mitanni in the fourteenth century BC.

Reign

He is known only from a single mention in a tablet found in Tell Brak "Artassumara the king, son of Shut ...

, was murdered in the 14th century BC, which led to the accession of the otherwise minor figure Tushratta

Tushratta (Akkadian: and ) was a king of Mitanni, c. 1358–1335 BCE, at the end of the reign of Amenhotep III and throughout the reign of Akhenaten. He was the son of Shuttarna II. Tushratta stated that he was the grandson of Artatama I. His si ...

. Tushratta's rise to power led to internal conflict within the Mittani kingdom as different factions vied with each other to depose him. During the wars that followed Tushratta's accession, multiple rivals came to rule Mitanni, such as Artatama II Artatama II was a brief usurper to the throne of king Tushratta of Mitanni in the fourteenth century BC. He may have been a brother of Tushratta or belonged to a rival line of the royal house. His son, Shuttarna III, ruled Mitanni after him.Pruzsin ...

and Shuttarna III

Shuttarna III was a Mitanni king who reigned for a short period in the 14th century BC. He was the son of Artatama II, a usurper to the throne of Tushratta.

At that time, Assyria, led by Ashur-uballit I, became more powerful. But also Babylon, le ...

. The Assyrians sometimes fought them and sometimes allied with them. Shuttarna III secured Assyrian support, but had to pay heavily for it in silver and gold.

Arrapha

Arrapha or Arrapkha ( Akkadian: ''Arrapḫa''; ar, أررابخا ,عرفة) was an ancient city in what today is northeastern Iraq, thought to be on the site of the modern city of Kirkuk.

In 1948, ''Arrapha'' became the name of the residential ...

and Nuzi

Nuzi (or Nuzu; Akkadian Gasur; modern Yorghan Tepe, Iraq) was an ancient Mesopotamian city southwest of the city of Arrapha (modern Kirkuk), located near the Tigris river. The site consists of one medium-sized multiperiod tell and two small s ...

, which was destroyed by Assyrian troops in the 1330s BC or before. Neither city was formally incorporated into Assyria; the Assyrian army probably withdrew to the Little Zab, allowing Babylonia to conquer the sites. In the centuries to come, Assyrian kings often found themselves as rivals of the Babylonian kings

The king of Babylon (Akkadian: ''šakkanakki Bābili'', later also ''šar Bābili'') was the ruler of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Babylon and its kingdom, Babylonia, which existed as an independent realm from the 19th century BC to its fall ...

. Ashur-uballit himself did not wish to engage in long-lasting conflicts with the Babylonians, clearly illustrated since he married his daughter Muballitat-Serua to the Babylonian king Burnaburiash II

Burna-Buriaš II, rendered in cuneiform as ''Bur-na-'' or ''Bur-ra-Bu-ri-ia-aš'' in royal inscriptions and letters, and meaning ''servant'' or ''protégé of the Lord of the lands'' in the Kassite language, where Buriaš (, dbu-ri-ia-aš₂) is a ...

. Prior to achieving peace, Burnaburiash had been a prominent enemy of the Assyrians. At one point, he had attempted to tarnish Assyrian diplomatic and trade relations with Egypt by sending a letter to the pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: ''pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the an ...

Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Echnaton, Akhenaton, ( egy, ꜣḫ-n-jtn ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning "Effective for the Aten"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dy ...

wherein he falsely claimed that the Assyrians were his vassals. After several years of peaceful co-existence between Assyria and Babylonia, the Babylonian king Kara-hardash

Burna-Buriaš II, rendered in cuneiform as ''Bur-na-'' or ''Bur-ra-Bu-ri-ia-aš'' in royal inscriptions and letters, and meaning ''servant'' or ''protégé of the Lord of the lands'' in the Kassite language, where Buriaš (, dbu-ri-ia-aš₂) is a ...

, son of Burnaburiash and Muballitat-Serua, was overthrown. Muballitat-Serua was most likely killed at the same time, which prompted Ashur-uballit to march south and restore order. The usurper who had taken Babylonia in the meantime, Nazi-Bugash

Burna-Buriaš II, rendered in cuneiform as ''Bur-na-'' or ''Bur-ra-Bu-ri-ia-aš'' in royal inscriptions and letters, and meaning ''servant'' or ''protégé of the Lord of the lands'' in the Kassite language, where Buriaš (, dbu-ri-ia-aš₂) is a ...

, was overthrown and replaced by the Assyrians with Kurigalzu II

Kurigalzu II (c. 1332–1308 BC short chronology) was the 22nd king of the Kassite or 3rd dynasty that ruled over Babylon. In more than twelve inscriptions, Kurigalzu names Burna-Buriaš II as his father. Kurigalzu II was possibly placed on the ...

, another son of Burnaburiash.

Ashur-uballit's successors Enlil-nirari ( 1327–1318 BC) and Arik-den-ili

Arik-den-ili, inscribed mGÍD-DI-DINGIR, “long-lasting is the judgment of god,” was King of Assyria 1317–1306 BC, ruling the Middle Assyrian Empire. He succeeded Enlil-nirari, his father, and was to rule for twelve years and inaugurate the t ...

( 1317–1306 BC) were less successful than Ashur-uballit in expanding and consolidating Assyrian power, and as such the new kingdom developed somewhat haltingly and remained fragile. Kurigalzu did not remain loyal to the Assyrians and instead fought with Enlil-nirari. His treason and betrayal resulted in deep trauma, still referenced in Assyrian writings concerning diplomacy and wars against Babylonia more than a century later; it was seen by many later Assyrians as the starting point of the historical enmity between the two civilizations. At one point, Kurigalzu reached as far into the Assyrian lands as Sugagu, a settlement located only a day's journey

A day's journey in pre-modern literature, including the Bible, ancient geographers and ethnographers such as Herodotus, is a measurement of distance.

In the Bible, it is not as precisely defined as other Biblical measurements of distance; the dis ...

from Assur. Although the Assyrians drove him away, an incursion this deep into the Assyrian heartland left an impression on the Assyrians, who in future conflicts often focused on Babylonian border outposts along the eastern Tigris river as a preventive measure.

First period of expansion and consolidation

Reigns of Adad-nirari I and Shalmaneser I

Under the warrior-kings Adad-nirari I ( 1305–1274 BC),

Under the warrior-kings Adad-nirari I ( 1305–1274 BC), Shalmaneser I

Shalmaneser I (𒁹𒀭𒁲𒈠𒉡𒊕 md''sál-ma-nu-SAG'' ''Salmanu-ašared''; 1273–1244 BC or 1265–1235 BC) was a king of Assyria during the Middle Assyrian Empire. Son of Adad-nirari I, he succeeded his father as king in 1265 BC.

Accord ...

( 1273–1244 BC) and Tukulti-Ninurta I

Tukulti-Ninurta I (meaning: "my trust is in he warrior godNinurta"; reigned 1243–1207 BC) was a king of Assyria during the Middle Assyrian Empire. He is known as the first king to use the title "King of Kings".

Biography

Tukulti-Ninurta I su ...

( 1243–1207 BC), Assyria began to realize its aspirations of becoming a significant regional power. Though the other powers of the Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

, such as Egypt, the Hittites and Babylonia, had at first been reluctant to view the new Assyrian kingdom as their equal, from the time of Adad-nirari I onwards, when Assyria grew to take the place of Mitanni, its status as one of the major kingdoms became undeniable. Adad-nirari I was the first Assyrian king to march against the remnants of the Mitanni kingdom and the first Assyrian king to include lengthy narratives of his campaigns in his royal inscriptions. Adad-nirari early in his reign defeated Shattuara I of Mitanni and forced him to pay tribute to Assyria as a vassal ruler. Given that the Assyrian army extensively plundered and destroyed portions of Mitanni during this campaign, it is unlikely that there at this point were any plans to outright annex and consolidate the Mitanni lands. Sometime later, Shattuara's son Wasashatta

Wasashatta, also spelled Wasašatta, was a king of the Hurrian kingdom of Mittani ca. the early thirteenth century BC.

Like his father Shattuara, Wasashatta was an Assyrian vassal. He revolted against his master Adad-nirari I (c. 1295-1263 BC ( ...

rebelled against the Assyrians, though was defeated by Adad-nirari who, as punishment, annexed several cities alongside the Khabur river. At Taite Taite (called ''Taidu'' in Assyrian sources) was one of the capitals of the Mitanni Empire. Its exact location is still unknown, although it is speculated to be in the Khabur region. The site of Tell Hamidiya (Tall al-hamidiya) has recently been id ...

, a former Mitanni capital, Adad-nirari constructed a royal palace for himself.

The primary focus of Adad-nirari was the conquest and/or pacification of Babylonia. Not only did Babylonia present a more immediate threat, but conquering southern Mesopotamia would also be more prestigious. Through military focus on Babylonian border towns, such as Lubdi and Rapiqu, it is clear that Adad-nirari's ultimate goal was to subdue the Babylonians and achieve hegemony over all of Mesopotamia. Adad-nirari's temporary occupations of Lubdi and Rapiqu were met with an attack by the Babylonian king Nazi-Maruttash

Nazi-Maruttaš, typically inscribed ''Na-zi-Ma-ru-ut-ta-aš'' or m''Na-zi-Múru-taš'', ''Maruttaš'' (a Kassite god synonymous with Ninurta) ''protects him'', was a Kassite king of Babylon c. 1307–1282 BC (short chronology) and self-proclaimed ...

, though Adad-nirari defeated him at the Battle of Kār Ištar 1280 BC and the Assyro-Babylonian border was redrawn in Assyria's favor. Under Adad-nirari's son Shalmaneser I, Assyrian campaigns against its neighbors and equals intensified. According to his own inscriptions, Shalmaneser conquered eight countries (likely minor states) in the first year of his reign. Among the sites captured was the fortress Arinnu, which Shalmaneser razed to the ground and turned into dust. Some of the dust from Arinnu was collected and symbolically brought back to Assur.

After the new Mitanni king Shattuara II Shattuara II, also spelled Šattuara II, was the last known king of the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni (Hanigalbat) in the thirteenth century BC, before the Assyrian conquest.

A king named Shattuara is suggested to have ruled Hanigalbat during the reig ...

rebelled against Assyrian authority, assisted by the Hittites, further campaigns were conducted against Mitanni in order to suppress the resistance. Shalmaneser's campaign against Mitanni was a great success; the Mitanni capital of Washukanni

Washukanni (also spelled Waššukanni) was the capital of the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni, from around 1500 BC to the 13th century BC.

Location

The precise location of Waššukanni is unknown. A proposal by Dietrich Opitz located it under the lar ...

was sacked and, realizing that the Mitanni lands were clearly not controllable through allowing the local rulers to continue to govern as vassals, the kingdom's lands were with some reluctance annexed into the Assyrian kingdom. The lands were not annexed directly into the royal domains, but rather placed under the rule of a viceroy who bore the title of grand vizier

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first ...

and king of Hanigalbat. The first such ruler was Shalmaneser's brother, Ibashi-ili, whose descendants later continued to occupy the position. This arrangement, placing the Mitanni lands under the rule of a lesser branch of the royal family, suggests that the Assyrian elites in the heartland had only a marginal interest in the new conquests. Though Shalmaneser boasted of brutal acts against the defeated Mitanni armies, in one inscription claiming to have blinded over 14,000 prisoners of war, he was also one of the first Assyrian kings to take prisoners in the first place instead of simply executing captured enemies. Adad-nirari was also a great builder; among his most significant construction projects was the construction of the city of Nimrud

Nimrud (; syr, ܢܢܡܪܕ ar, النمرود) is an ancient Assyrian city located in Iraq, south of the city of Mosul, and south of the village of Selamiyah ( ar, السلامية), in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a m ...

, a highly significant site in later Assyrian history.

Under Shalmaneser, the Assyrians also conducted significant campaigns against the Hittites. Already in the time of Adad-nirari, Assyrian envoys had been treated poorly at the court of the Hittite king Mursili III

Mursili III, also known as Urhi-Teshub, was a king of the Hittites who assumed the throne of the Hittite empire (New Kingdom) at Tarhuntassa upon his father's death. He was a cousin of Tudhaliya IV and Queen Maathorneferure. He ruled ca. 1282– ...

. When Mursili's successor Hattusili III Ḫattušili (''Ḫattušiliš'' in the inflected nominative case) was the regnal name of three Hittite kings:

* Ḫattušili I (Labarna II)

* Ḫattušili II

* Ḫattušili III

It was also the name of two Neo-Hittite kings:

* Ḫattušili I (Laba ...

reached out to Shalmaneser in an attempt to forge an alliance, probably due to recent losses against Egypt, he was insultingly rejected and called a "substitute of a great king". The strained relations between the two empires sometimes erupted into war; Shalmaneser warred several times against Hittite vassal states in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

. The hostilities reached their zenith under Shalmaneser's son and successor Tukulti-Ninurta I, who defeated the Hittites at the Battle of Nihriya

The Battle of Niḫriya was the culminating point of the hostilities between the Hittites and the Assyrians for control over the remnants of the former empire of Mitanni.

When Hittite king Šuppiluliuma I (r. c. 1344–1322 BC) conquered Mitanni, ...

1237 BC. The Hittite defeat at Nihriya marked the beginning of the end of their influence in northern Mesopotamia.

Reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I

Tudḫaliya IV

Tudhaliya IV was a king of the Hittite Empire (New kingdom), and the younger son of Hattusili III. He reigned c. 1245–1215 BC (middle chronology) or c. 1237–1209 BC (short chronology). His mother was the great queen, Puduhepa.

Biograph ...

sent him a letter of congratulations but secretly also sent a letter to the Assyrian grand vizier

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first ...

Babu-aha-iddina in which he implored the vizier to dissuade Tukulti-Ninurta from attacking the Hittite territories in the mountains northwest of Assyria and to work on improving relations. Tudḫaliya's letter did little to dissuade him, who saw through the empty flatteries and attacked and conquered the lands in question in his first few years as king. According to his inscriptions, the conquest was widely celebrated as one of his outstanding early achievements.

As for his predecessors, Tukulti-Ninurta's main focus was on Babylonia. His first act in regard to his southern neighbor, Kashtiliash IV

Kaštiliašu IV was the twenty-eighth Kassite king of Babylon and the kingdom contemporarily known as Kar-Duniaš, c. 1232–1225 BC ( short chronology). He succeeded Šagarakti-Šuriaš, who could have been his father, ruled for eight years,Ki ...

, was to escalate conflict through claiming "traditionally Assyrian" lands along the eastern Tigris. Tukulti-Ninurta shortly thereafter invaded Babylonia through what modern historians generally regard to be an unprovoked attack. In the contemporary '' Tukulti-Ninurta Epic'', a propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

epic used to justify his exploits, the king is described as acting according to divine order against Kashtiliash, who is described as vile ruler, abandoned by the gods. In the text, he is accused of various atrocities, including attacking Assyria, violating temples, and deporting or killing civilians. Though there is no evidence for these accusations, they might well have been based on real events, albeit probably exaggerated. According to the ''Tukulti-Ninurta'' epic, he marched south to the Diyala River and began targeting Babylonian cities, including Sippar

Sippar ( Sumerian: , Zimbir) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its '' tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah near Yusufiyah in Iraq's Baghdad Governorate, som ...

and Dur-Kurigalzu

Dur-Kurigalzu (modern ' in Baghdad Governorate, Iraq) was a city in southern Mesopotamia, near the confluence of the Tigris and Diyala rivers, about west of the center of Baghdad. It was founded by a Kassite king of Babylon, Kurigalzu I (died ...

. Kashtiliash then attacked the Assyrians, confident that he would be victorious, but he was defeated and then avoided conflict himself for the rest of the war. Tukulti-Ninurta eventually emerged as the winner, conquering Babylonia 1225 BC, dragging Kashtiliash back to Assyria as a prisoner, and assuming the ancient title "king of Sumer and Akkad

King of Sumer and Akkad ( Sumerian: ''lugal-ki-en-gi-ki-uri'', Akkadian: ''šar māt Šumeri u Akkadi'') was a royal title in Ancient Mesopotamia combining the titles of "King of Akkad", the ruling title held by the monarchs of the Akkadian E ...

". Given that some inscriptions report "Assyrian refugees" from Babylonia and that some soldiers were "starving", it appears that the victory was a costly one. Tukulti-Ninurta's rule over Babylonia, which nominally placed territories as far south as the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Persis, Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a Mediterranean sea (oceanography), me ...

under Assyrian rule, lasted for several years and began the apex of Middle Assyrian power, though Assyrian domination appears to have been rather indirect.

Tukulti-Ninurta experienced some difficulties in keeping his empire together, particularly in Babylonia. Though the period after Kashtiliash's deposition is poorly attested in Babylonia, it appears that there was a second Assyrian campaign directed towards the south 1222 BC, after the rule of Tukulti-Ninurta's vassal kings Enlil-nadin-shumi

Enlil-nādin-šumi, inscribed mdEN.LĺL-MU-MUKinglist A, BM 33332, ii 8. or mdEN.LĺL''-na-din-''MU,Chronicle P, BM 92807, iv 14, 16. meaning “Enlil is the giver of a name,” was a king of Babylon, c. 1224 BC, following the overthrow of K ...

and Kadashman-Harbe II

Kadašman-Ḫarbe II, inscribed d''Ka-dáš-man-Ḫar-be'', ''Kad-aš-man-Ḫar-be'' or variants and meaning ''I believe in Ḫarbe'', the lord of the Kassite pantheon corresponding to Enlil, succeeded Enlil-nādin-šumi, as the 30th Kassite or ...

, which resulted in the accession of another vassal, Adad-shuma-iddina

Adad-šuma-iddina, inscribed mdIM-MU-SUM''-na'', ("Adad has given a name") and dated to around ca. 1222–1217 BC (short chronology), was the 31st king of the 3rd or Kassite dynasty of Babylon''Kinglist A'', BM 33332, ii 10. and the country conte ...

. Because Tukulti-Ninurta was able to come to Babylon as a guest in 1221 BC and make offerings to the Babylonian gods, it is clear that Adad-shuma-iddina enjoyed Assyrian support for his rule. Though this campaign was followed by several years of peace, it is clear that Adad-shuma-iddina eventually stopped acting like a puppet ruler. Though Tukulti-Ninurta forgave him for a revolt in which he seized the city of Lubdi, a second revolt by Adad-shuma-iddina in 1217 BC was met with a third campaign against Babylon, in which Tukulti-Ninurta looted the city and carried off the religiously important Statue of Marduk

The Statue of Marduk, also known as the Statue of Bêl ('' Bêl'', meaning "lord", being a common designation for Marduk), was the physical representation of the god Marduk, the patron deity of the ancient city of Babylon, traditionally housed in ...

(Marduk

Marduk (Cuneiform: dAMAR.UTU; Sumerian: ''amar utu.k'' "calf of the sun; solar calf"; ) was a god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon. When Babylon became the political center of the Euphrates valley in the time of ...

being Babylonia's national deity) to Assyria. He assumed the further style "king of the extensive mountains and plains" and claimed to rule from the "Upper Sea

Upper may refer to:

* Shoe upper or ''vamp'', the part of a shoe on the top of the foot

* Stimulant, drugs which induce temporary improvements in either mental or physical function or both

* ''Upper'', the original film title for the 2013 found f ...

to the Lower Sea

Lower may refer to:

*Lower (surname)

*Lower Township, New Jersey

*Lower Receiver (firearms)

*Lower Wick

Lower Wick is a small hamlet located in the county of Gloucestershire, England. It is situated about five miles south west of Dursley, eig ...

" and that he received tribute " from the four quarters". In one of his inscriptions, Tukulti-Ninurta went as far as proclaiming himself to be the sun-god Shamash

Utu (dUD "Sun"), also known under the Akkadian name Shamash, ''šmš'', syc, ܫܡܫܐ ''šemša'', he, שֶׁמֶשׁ ''šemeš'', ar, شمس ''šams'', Ashurian Aramaic: 𐣴𐣬𐣴 ''š'meš(ā)'' was the ancient Mesopotamian sun god. ...

incarnated, titling himself ''šamšu kiššat niše'' ("sun odof all people"). This claim was highly unusual for an Assyrian king to make as the Assyrian rulers were generally not regarded to be divine figures themselves.

The last Babylonian campaign did not resolve all of Tukulti-Ninurta's problems; the Assyrian army at times had to be deployed to the mountains to the northwest and northeast of the Assyrian heartland to quell uprisings and soon enough, a Babylonian uprising led by Adad-shuma-usur

Adad-šuma-uṣur, inscribed dIM-MU-ŠEŠ, meaning "O Adad, protect the name!," and dated very tentatively ca. 1216–1187 BC (short chronology), was the 32nd king of the 3rd or Kassite dynasty of Babylon and the country contemporarily known as Ka ...

, perhaps a son of Kashtiliash IV, drove the Assyrians out of Babylonia 1216 BC. Tukulti-Ninurta is recorded to have complained to the Hittite king Šuppiluliuma II, at this point an ally of Assyria and expected to cooperate militarily, that he had "remained silent" on the "illegal seizure of power" of Adad-shuma-usur.

In addition to his campaigns and conquests, Tukulti-Ninurta is also famous for the most dramatic construction project of the entire Middle Assyrian period: the construction of a new capital city, Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, named after himself (the name meaning "fortress of Tukulti-Ninurta"). Founded in the eleventh year of his reign ( 1233 BC), the construction and brief occupation of the city was the only time the Assyrian capital was moved before the Neo-Assyrian

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

period, centuries later. After Tukulti-Ninurta's death, the capital was transferred back to Assur.

First period of decline

Inscriptions from the late reign of Tukulti-Ninurta showcase increasing internal isolation, as many among the powerful nobility of Assyria grew dissatisfied with his rule, especially after the loss of Babylonia. In some of his own inscriptions, Tukulti-Ninurta appears to lament the losses since his glory days. His long and prosperous reign ended with his assassination, which was followed by inter-dynastic conflict and a significant drop in Assyrian power. Though some historians have attributed the assassination to Tukulti-Ninurta's moving the capital away from Assur, a possibly sacrilegious act, it is more probable that it was the result of the growing dissatisfaction during his late reign. Later chroniclers blame the assassination on his son Ashur-nasir-apli, perhaps a misspelled version of the name of his successor

Inscriptions from the late reign of Tukulti-Ninurta showcase increasing internal isolation, as many among the powerful nobility of Assyria grew dissatisfied with his rule, especially after the loss of Babylonia. In some of his own inscriptions, Tukulti-Ninurta appears to lament the losses since his glory days. His long and prosperous reign ended with his assassination, which was followed by inter-dynastic conflict and a significant drop in Assyrian power. Though some historians have attributed the assassination to Tukulti-Ninurta's moving the capital away from Assur, a possibly sacrilegious act, it is more probable that it was the result of the growing dissatisfaction during his late reign. Later chroniclers blame the assassination on his son Ashur-nasir-apli, perhaps a misspelled version of the name of his successor Ashur-nadin-apli

Aššūr-nādin-apli, inscribed m''aš-šur-''SUM-DUMU.UŠ, was king of Assyria (1206 BC – 1203 BC or 1196 BC – 1194 BC short chronology). The alternate dating is due to uncertainty over the length of reign of a later monarch, Ninurta-apal-Ekur ...

( 1206–1203 BC). Another leader of the conspiracy appears to have been the grand vizier and vassal king of Hanigalbat Ili-ipadda, who retained a prominent position at the court for years thereafter. Ashur-nadin-apli was after his short reign succeeded by two of his brothers, Ashur-nirari III

Aššur-nerari III, inscribed m''aš-šur-''ERIM.GABA, “ Aššur is my help,” was king of Assyria (1202–1197 BC or 1193–1187 BC). He was the grandson of Tukulti-Ninurta I and might have succeeded his uncle or more probably his father Ashu ...

( 1202–1197 BC) and Enlil-kudurri-usur

Enlil-kudurrī-uṣur, md''Enlil''(be)''-ku-dúr-uṣur'', (Enlil protect the eldest son), was the 81st king of Assyria according to the Assyrian King List.''Assyrian King List'', iii 14.

Biography

Enlil-kudurri-usur was the son of Tukulti-Ninurt ...

( 1196–1192 BC), who also ruled only briefly and were unable to maintain Assyrian power. Though the line of Assyrian kings continued uninterrupted over the course of the decline, Assyria became restricted mostly to just the Assyrian heartland. The decline of the Middle Assyrian Empire broadly coincided with the Late Bronze Age collapse, a time when the Ancient Near East experienced monumental geopolitical changes; within a single generation, the Hittite Empire and the Kassite dynasty

The Kassite dynasty, also known as the third Babylonian dynasty, was a line of kings of Kassite origin who ruled from the city of Babylon in the latter half of the second millennium BC and who belonged to the same family that ran the kingdom of ...

of Babylon had fallen, and Egypt had been severely weakened through losing its lands in the Levant. Modern researchers tend to varyingly ascribe the collapse to large-scale migrations, invasions by the mysterious Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the Fren ...

, new warfare technology and its effects, starvation, epidemics, climate change and unsustainable exploitation of the working population.

Enlil-kudurri-usur

Enlil-kudurrī-uṣur, md''Enlil''(be)''-ku-dúr-uṣur'', (Enlil protect the eldest son), was the 81st king of Assyria according to the Assyrian King List.''Assyrian King List'', iii 14.

Biography

Enlil-kudurri-usur was the son of Tukulti-Ninurt ...

enjoyed a much poorer relationship with the line of vassal rulers of Hanigalbat, perhaps because he might not have supported the assassination of his father. Such a poor relationship was dangerous given that these vassal rulers were also members of the Assyrian royal family, as descendants of Adad-nirari I. At some point during Enlil-kudurri-usur's reign, Ili-ipadda's son Ninurta-apal-Ekur

Ninurta-apal-Ekur, inscribed mdMAŠ-A-''é-kur'', meaning “Ninurta is the heir of the Ekur,” was a king of Assyria in the early 12th century BC who usurped the throne and styled himself king of the universe and priest of the gods Enlil and Ninu ...

traveled to Babylonia where he met with Adad-shuma-usur. With Babylonian support, Ninurta-apal-Ekur then invaded Assyria and defeated Enlil-kudurri-usur in battle. According to the Babylonian Chronicles

The Babylonian Chronicles are a series of tablets recording major events in Babylonian history. They are thus one of the first steps in the development of ancient historiography. The Babylonian Chronicles were written in Babylonian cuneiform, f ...

, he was captured and surrendered to the Babylonians by his own people. Ninurta-apal-Ekur then became king, ending the line of rulers who were direct descendants of Tukulti-Ninurta. During his reign, 1191–1179 BC, Ninurta-apal-Ekur proved to be, like his immediate predecessors, unable to do much about the collapse of the empire. In the reign of his son, Ashur-dan I

Aššur-dān I, m''Aš-šur-dān''(kal)an, was the 83rd king of Assyria, reigning for 46Khorsabad King List and the SDAS King List both read, iii 19, 46 MU.MEŠ KI.MIN. (variant: 36Nassouhi King List reads, 26+x MU. EŠ LUGAL-ta DU.uš.) years, c. ...

( 1178–1133 BC), the situation improved somewhat as can be gathered from a campaign directed by Ashur-dan I against the Babylonian king Zababa-shuma-iddin, illustrating that hopes for gaining control of at least some southern lands and reasserting superiority over Babylonia had not been completely abandoned.

After Ashur-dan's death in 1133 BC, his two sons Ninurta-tukulti-Ashur

Ninurta-tukultī-Aššur, inscribed md''Ninurta''2''-tukul-ti-Aš-šur'', was briefly king of Assyria 1132 BC, the 84th to appear on the Assyrian Kinglist, marked as holding the throne for his ''ṭuppišu'', "his tablet," a period thought to corr ...

and Mutakkil-Nusku

Mutakkil-Nusku, inscribed m''mu-ta''/''tak-kil-''dPA.KU, "he whom Nusku endows with confidence," was king of Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian ...

struggled for power, with Mutakkil-Nusku emerging victorious but then only ruling for less than a year. Mutakkil-Nusku began a conflict with the Babylonian king Itti-Marduk-balatu

Itti-Marduk-balāṭu may refer to

Known period

* Itti-Marduk-balāṭu (vizier), vizier to Kassite Babylonian king Kadašman-Enlil II, ca. 1263 BC

* Itti-Marduk-balāṭu (eunuch), Kassite Babylonian king Meli-Šipak’s (ca. 1186–1172 BC) e ...

over control of the city of Zanqi or Zaqqa, which continued in the reign of his son and successor Ashur-resh-ishi I (1132–1115 BC). In the Synchronistic History (a later Assyrian document), further tensions at Zanqi are described between Ashur-resh-ishi and the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar I

Nebuchadnezzar I or Nebuchadrezzar I (), reigned 1121–1100 BC, was the fourth king of the Second Dynasty of Isin and Fourth Dynasty of Babylon. He ruled for 22 years according to the ''Babylonian King List C'', and was the most prominent monarc ...

, which included a battle in which the Babylonians burned down their own siege engine

A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent heavy castle doors, thick city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare. Some are immobile, constructed in place to attack enemy fortifications from a distance, while oth ...

s so that they would not be captured by the Assyrians. Though the Synchronistic History describes Assyria as in danger of Babylonian aggression in the reign of Nebuchadnezzar's father and predecessor Ninurta-nadin-shumi

Ninurta-nādin-šumi, inscribed mdMAŠ-''na-din''-MUBabylonian ''King List C'', 3. or dNIN.IB-SUM-MU,Dagger, Musée du Louvre, L. 36 cm; another dagger on Tehran art market. “Ninurta (is) giver of progeny,” 1127–1122 BC, was the 3rd king o ...

, it casts Ashur-resh-ishi as a savior of the empire, who defeated Nebuchadnezzar in several battles and was able to defend the southern Assyrian border. Ashur-resh-ishi as such began to reverse the decades of Assyrian decline and in his inscriptions claimed the epithet "avenger of Assyria" (''mutēr gimilli māt Aššur'').

Second period of expansion and consolidation

Ashur-resh-ishi's son and successor

Ashur-resh-ishi's son and successor Tiglath-Pileser I

Tiglath-Pileser I (; from the Hebraic form of akk, , Tukultī-apil-Ešarra, "my trust is in the son of Ešarra") was a king of Assyria during the Middle Assyrian period (1114–1076 BC). According to Georges Roux, Tiglath-Pileser was "one of ...

(1114–1076 BC) inaugurated a second period of Middle Assyrian ascendancy. Owing to his father's victories against Babylon, Tiglath-Pileser was free to divert his attention to other regions and not worry about a southern attack. Texts written already during his first few regnal years demonstrate that Tiglath-Pileser ruled with more confidence than his predecessors, using titles such as "unrivalled king of the universe, king of the four quarters

King of the Four Corners of the World ( Sumerian: ''lugal-an-ub-da-limmu-ba'', Akkadian: ''šarru kibrat 'arbaim'', ''šar kibrāti arba'i'', or ''šar kibrāt erbetti''), alternatively translated as King of the Four Quarters of the World, King ...

, king of all princes, lord of lords" and epithets such as "splendid flame which covers the hostile land like a rain storm". In his first year as king, Tiglath-Pileser defeated the Mushki

The Mushki (sometimes transliterated as Muški) were an Iron Age people of Anatolia who appear in sources from Assyria but not from the Hittites. Several authors have connected them with the Moschoi (Μόσχοι) of Greek sources and the Geor ...

, a tribe who had taken control of various lands in the north fifty years prior. The inscriptions mention that no king had defeated them in battle before and that their 20,000 men strong army, led by five kings, was defeated by Tiglath-Pileser, who however allowed the 6,000 surviving enemies to settle in Assyria as his subjects. One of the Mushki strongholds, the city of Katmuḫu in the northeast, continued to be troublesome for a few years before it was reconquered, looted and its king, Errupi, was deported. Numerous other sites in the northeast were also conquered and incorporated into his empire.

Tiglath-Pileser also went on significant campaigns in the west. The cities of northern Syria, which had ceased to pay tribute decades prior, were reconquered and the Kaskians

The Kaska (also Kaška, later Tabalian Kasku and Gasga,) were a loosely affiliated Bronze Age non-Indo-European tribal people, who spoke the unclassified Kaskian language and lived in mountainous East Pontic Anatolia, known from Hittite sour ...

and Urumeans

The Urumu (often transliterated as Urumeans) were a tribe attested in cuneiform sources in the Bronze Age. They are often considered to be one of the ancestors of the Armenians being one of the tribes which were part of the Armenian Hayasa-Azzi ...

, tribes who had also settled in the region, voluntarily submitted to him immediately upon the arrival of his army. He also waged war on the Nairi

Nairi ( classical hy, Նայիրի, ''Nayiri'', reformed: Նաիրի, ''Nairi''; , also ''Na-'i-ru'') was the Akkadian name for a region inhabited by a particular group (possibly a confederation or league) of tribal principalities in the Armen ...

people in the Armenian highlands. Famed for their knowledge of horse breeding, his self-admitted goal of this campaign was to acquire more horses for the Assyrian army. It is clear from his inscriptions that the goal of the campaigns were to instill respect among the rulers of the lands formerly subordinate to Assyria, to reconquer the old Assyrian borders, and to go beyond them; "Altogether, I conquered 42 lands and their rulers from the other side of the Lower Zab in distant mountainous regions to the other side of the Euphrates River, people of Ḫatti, and the Upper Sea in the west – from my accession year to my fifth regnal year. I subdued them to one authority, took hostages from them, (and) imposed upon them tribute and impost".

Tiglath-Pileser's inscriptions are the first Assyrian inscriptions to describe punitive measures against rebelling cities and regions in any detail. A more important innovation was increasing the size of the Assyrian cavalry and introducing war chariots

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&nb ...

on a grander scale than previous kings. Chariots were also increasingly used by Assyria's enemies. In the final years of his reign, he twice engaged the Babylonian king Marduk-nadin-ahhe

Marduk-nādin-aḫḫē, inscribed mdAMAR.UTU''-na-din-''MU, reigned 1095–1078 BC, was the sixth king of the Second Dynasty of Isin and the 4th Dynasty of Babylon.''Babylonian King List C'', line 6. He is best known for his restoration of the ...

in battles with a great number of chariots. Though he did not conquer Babylonia, several cities, including Babylon itself, were successfully attacked and looted. He was probably unable to conquer Babylonia since a significant amount of attention needed to be diverted to the Aramean

The Arameans ( oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; syc, ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ, Ārāmāyē) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East, first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. The Aramean ...

tribes in the west. Though he was one of the most powerful kings of the Middle Assyrian period, succeeding in imposing tribute from as far away as Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

, his achievements were not long-lasting and several territories, especially in the west, were likely lost again before his death.

As a result of Tiglath-Pileser's campaigns, Assyria became somewhat overstretched and his successors had to adapt to be on the defensive. His son and successor Asharid-apal-Ekur Ašarēd-apil-Ekur, inscribed m''a-šá-rid-''A-É.KURKhorsabad Kinglist: iii 41. or mSAG.KAL-DUMU.UŠ-É.KURSDAS Kinglist iii 27. and variants,Nassouhi Kinglist iv 8: mS.html" ;"title="sup>mS">sup>mSG-A-É.KUR. meaning “the heir of the Ekur is ...

(1075–1074 BC) ruled too briefly to do anything and his successor Ashur-bel-kala

Aššūr-bēl-kala, inscribed m''aš-šur-''EN''-ka-la'' and meaning “ Aššur is lord of all,” was the king of Assyria 1074/3–1056 BC, the 89th to appear on the ''Assyrian Kinglist''. He was the son of Tukultī-apil-Ešarra I, succeeded his ...

(1073–1056 BC), another son of Tiglath-Pileser, managed to only briefly follow in his father's footsteps. Ashur-bel-kala campaigned in the mountains to the northeast and the Levant and is recorded to have received gifts from Egypt. Though political objectives had thus not changed since Tiglath-Pileser's time, Ashur-bel-kala too had to divert significant attention to the Arameans. Due to the Aramean tactics of avoiding open battle and instead attacking the Assyrians in numerous minor skirmishes, the Assyrian army could not take advantage of their technical and numerial superiority. The Arameans were not Ashur-bel-kala's only enemies in the west, given that he is also recorded to have fought against Tukulti-Mer, king of Mari. The conflict with Marduk-nadin-ahhe in Babylonia continued under Ashur-bel-kala, though it was eventually resolved diplomatically. After the death of Marduk-nadin-ahhe's successor Marduk-shapik-zeri

Marduk-šāpik-zēri, inscribed in cuneiform dAMAR.UTU-DUB-NUMUN or phonetically ''-ša-pi-ik-ze-ri'', and meaning “ Marduk (is) the outpourer of seed”, reigned 1077–1065 BC, was the 7th king of the 2nd dynasty of Isin and 4th dynasty of ...

in 1065 BC, Ashur-bel-kala was even able to intervene and install the unrelated Adad-apla-iddina as king of Babylon. Adad-apla-iddina's daughter then married Ashur-bel-kala, bringing peace to the two kingdoms. Though he shared his father's ambition, and claimed the title "lord of all" after his victorious campaigns in Syria, Babylonia and the northeastern mountains, Ashur-bel-kala was ultimately unable to surpass Tiglath-Pileser and his successes were built on shaky foundations.

Second period of decline

Century of crisis

Ashur-bel-kala's son and successorEriba-Adad II Erība-Adad II, inscribed mSU-dIM, “Adad has replaced,” was the king of Assyria 1056/55–1054 BC, the 94th to appear on the ''Assyrian Kinglist''.''SDAS Kinglist'', iii 31.''Nassouhi Kinglist'', iv 12. He was the son of Aššur-bēl-kala whom ...

(1056–1054 BC), and generations of kings thereafter, were unable to maintain the achievements of their predecessors. The period of decline initiated after Ashur-bel-kala's death was not reversed until the middle of the 10th century BC. Though this period is poorly documented, it is clear that Assyria underwent a major crisis.

Although Assyria was only marginally affected by the Late Bronze Age collapse, the collapse caused great changes in the geopolitics of the lands surrounding Assyria. In large part, the power vacuum

In political science and political history, the term power vacuum, also known as a power void, is an analogy between a physical vacuum to the political condition "when someone in a place of power, has lost control of something and no one has repla ...

left by the Hittites and Egyptians in Anatolia and the Levant allowed various ethno-tribal communities and states to take their place. In northern Anatolia and northern Syria, the Luwians

The Luwians were a group of Anatolian peoples who lived in central, western, and southern Anatolia, in present-day Turkey, during the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. They spoke the Luwian language, an Indo-European language of the Anatolian sub-fam ...

seized power, forming the Syro-Hittite states

The states that are called Syro-Hittite, Neo-Hittite (in older literature), or Luwian-Aramean (in modern scholarly works), were Luwians, Luwian and Arameans, Aramean regional polities of the Iron Age, situated in southeastern parts of modern Turke ...

. In Syria, the Arameans grew increasingly prominent. In Palestine, the Philistines

The Philistines ( he, פְּלִשְׁתִּים, Pəlīštīm; Koine Greek (LXX): Φυλιστιείμ, romanized: ''Phulistieím'') were an ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan from the 12th century BC until 604 BC, when ...

and Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...